30 SECOND NOTES: The cost of prejudice is exemplified by the life of Florence Beatrice Price. Price, a Black woman of exceptional talent, education, determination and character, had significant professional successes, but her career and reputation were unjustly limited by the virulent racism of Jim Crow America. As her works, such as Dances in the Canebrakes, have finally been recognized with performances in concert halls during the last decade, it has become clear that one of the most original and brilliant voices in American music was silenced for more than a century. When Ludwig van Beethoven left his native Bonn to settle permanently in Vienna in 1792, he first established his reputation in the city as a pianist of passionate, almost untamed character. It was for his own appearances that Beethoven composed his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1795, containing it within classical formal parameters but previewing in it the heightened expression that would later make him the master composer of the age. In the Symphonic Dances of 1940, the last of his orchestral works, Sergei Rachmaninoff confirmed again not just the stylistic tradition of 19th-century Romanticism in his music but also its creative philosophy: “I try to make music speak directly and simply that which is in my heart. If there is love there, or bitterness, or sadness, or religion, these moods become part of my music, and it becomes either beautiful or bitter or sad or religious.”

FLORENCE B. PRICE

- Born April 9, 1888 in Little Rock, Arkansas;

- died June 3, 1953 in Chicago.

DANCES IN THE CANEBRAKES

- Orchestral version first performed in June 1998 in Flagstaff, Arizona, conducted by John McLaughlin Williams.

- These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 9 minutes)

Florence B. Price was a musical pioneer — one of the first African-American students to graduate from the New England Conservatory of Music, the first African-American woman to have a symphonic work performed by a major American orchestra and the first winner of the composition contest sponsored by the progressive Wanamaker Foundation.

Florence Beatrice Smith was born in 1888 into the prosperous and culturally engaged family of a dentist in Little Rock, Arkansas. She received her first piano lessons from her mother, a schoolteacher and singer, and Florence first played in public at age four. She later took up organ and violin, and at age fourteen she was admitted to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. There, she studied with George Chadwick and Frederick Converse, two of the generation’s leading composers, wrote her first string trio and a symphony (now lost), and graduated in 1907 with honors with both an artist diploma in organ and a teaching certificate. She returned to Arkansas, where she taught at Arkadelphia Academy and Shorter College before being appointed music department chairman at Clark University in Atlanta in 1910. She returned to Little Rock two years later to marry attorney Thomas J. Price. She left classroom teaching to devote herself to raising two daughters and gave private instruction in violin, organ, piano, and composing.

In 1927, following racial unrest in Arkansas that included a lynching, the Price family moved to Chicago, where Florence studied composition, orchestration, organ, languages and liberal arts at various schools with several of the city’s leading musicians and teachers. Black culture and music flourished in Chicago — jazz, blues, spirituals, popular, theater, classical — educational opportunities were readily available, recording studios were established, the National Association of Negro Musicians was founded there in 1919, and Price took advantage of everything. She ran a successful piano studio, wrote educational pieces for her students, published gospel and folksong arrangements, composed popular songs (under the pseudonym VeeJay), and performed as a church and theater organist. Among her many friends were the physician Dr. Monroe Alpheus Majors and his wife, organist and music teacher Estelle C. Bonds, and Price became both friend and teacher to their gifted daughter, Margaret. In 1932, Price and Bonds (then just nineteen) won respectively first and second prize in the Rodman Wanamaker Foundation Composition Competition, established to recognize classical compositions by Black composers, Price for her Symphony in E Minor and Piano Sonata and Bonds for her song Sea Ghost. The performance of Price’s Symphony on June 15, 1933 by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frederick Stock, was the first by a major American orchestra of a symphonic work by an African-American woman. Price continued to compose prolifically — three more symphonies and two more piano concertos, a Violin Concerto, chamber, piano and organ pieces, songs, spiritual arrangements, jingles for radio commercials — and received numerous performances, including her arrangement of the spiritual My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord that Marian Anderson used to close her historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. on April 9, 1939. Florence Price died in Chicago on June 3, 1953.

Price composed her three Dances in the Canebrakes for piano in 1953, rooting their style and expression, as was her usual practice, in the rhythms, melodic traits and ethos (but not in borrowed thematic material) of the African-American experience; they were orchestrated by William Grant Still, widely regarded as the “Dean of African-American Composers” until his death in Los Angeles in 1978. The first and last of the Dances in the Canebrakes — a “canebrake” is a dense stand of sugarcane, a staple crop on ante-bellum southern plantations — suggest a theatrical inspiration, Nimble Feet recalling the cakewalk, a popular 19th-century social dance in the South and in minstrel shows, and Silk Hat and Walking Cane, which sounds like a slow, nostalgic rag to accompany a nattily attired dancer. Tropical Noon is a languid and subtly syncopated evocation of a peaceful, mid-summer scene.

The score calls for piccolo, flute, two oboes, clarinet, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, two bassoons, three horns, three trumpets, two trombones, timpani, cymbals, snare drum, glockenspiel, vibraphone, triangle, castanets, claves, harp and the usual strings.

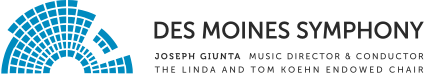

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

- Born December 16, 1770 in Bonn;

- died March 26, 1827 in Vienna.

PIANO CONCERTO NO.1 IN C MAJOR, OP.15

- First performed on December 18, 1795 in Vienna, with the composer as soloist.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on October 13, 1973 with Willis Page conducting. Four subsequent performances occurred, most recently on March 24 & 25, 2018 conducted by Joseph Giunta conducting with Christopher O’Riley as soloist.

(Duration: ca. 36 minutes)

“His genius, his magnetic personality were acknowledged by all, and there was, besides, a gaiety and animation about the young Beethoven that people found immensely attractive. The troubles of boyhood were behind him: his father had died very shortly after his departure from Bonn, and by 1795, his brothers were established in Vienna, Caspar Karl as a musician, Johann as an apothecary. During his first few months in the capital, he had indeed been desperately poor, depending very largely on the small salary allowed him by the Elector of Bonn. But that was all over now. He had no responsibilities, and his music was bringing in enough to keep him in something like affluence. He had a servant, for a short time he even had a horse; he bought smart clothes, he learned to dance (though not with much success), and there is even mention of his wearing a wig! We must not allow our picture of the later Beethoven to throw its dark colors over these years of his early triumphs. He was a young giant exulting in his strength and his success, and a youthful confidence gave him a buoyancy that was both attractive and infectious. Even in 1791, before he left Bonn, Carl Junker could describe him as ‘this amiable, lighthearted man.’ And in Vienna he had much to raise his spirits and nothing (at first) to depress them.” Peter Latham painted this cheerful picture of the young Beethoven as Vienna knew him during his twenties, the years before his deafness, his recurring illnesses and his titanic struggles with his mature compositions had produced the familiar dour figure of his later years.

Beethoven came to Vienna for good in 1792, having made an unsuccessful foray in 1787, and he quickly attracted attention for his piano playing. His appeal was in an almost untamed, passionate, novel quality in both his manner of performance and his personality, characteristics that first intrigued and then captivated those who heard him. It was for his own concerts that Beethoven composed the first four of his five mature piano concertos. (Two juvenile essays in the genre are discounted in the numbering.) The opening movement of the First Piano Concerto is indebted to Mozart for its handling of the concerto-sonata form, for its technique of orchestration, and for the manner in which piano and orchestra are integrated. Beethoven added to these quintessential qualities of the Classical concerto a wider-ranging harmony, a more openly virtuosic role for the soloist and a certain emotional weight characteristic of his large works. Beethoven molded the Largo to the songful aspect of his playing and reinforced that quality with lyrical solos for the clarinet. The rondo-finale is written in an infectious manner reminiscent of Haydn, brimming with high spirits and good humor.

The score calls for flute, pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets, timpani and the usual strings.

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF

- Born April 1, 1873 in Oneg (near Novgorod), Russia;

- died March 28, 1943 in Beverly Hills, California.

SYMPHONIC DANCES, OP. 45

- First performed on January 4, 1941 in Philadelphia, conducted by Eugene Ormandy.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on April 8, 1997 with Joseph Giunta conducting. Two subsequent performances occurred, the most recent on September 23 & 24, 2017 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 34 minutes)

World War I, of course, was a trial for Rachmaninoff and his Russian countrymen, but his most severe personal adversity came when the 1917 Revolution smashed the country’s aristocratic society — the only world he had ever known. He was forced to flee his beloved country for America and pined for his homeland the rest of his life. He did his best to keep the old language, food, customs and holidays alive in his own household, “but it was at best synthetic,” wrote American musicologist David Ewen. “Away from Russia, which he could never hope to see again, he always felt lonely and sad, a stranger even in lands that were ready to be hospitable to him. His homesickness assumed the character of a disease as the years passed, and one symptom of that disease was an unshakable melancholy.”

By 1940, when he composed the Symphonic Dances, he was worried over his daughter Tatiana, who was trapped in France by the German invasion (he never saw her again), and had been weakened by a minor operation in May. Still, he felt the need to compose for the first time since the Third Symphony of 1936. The three Symphonic Dances were written quickly at his summer retreat on Long Island Sound, an idyllic setting for composing, where he had a studio by the water in which to work in seclusion, lovely gardens for walking, and easy access to a ride in his new cabin cruiser, one of his favorite pastimes. Despite his pleasant surroundings, it was the man and not the setting that was expressed in this music. “I try to make music speak directly and simply that which is in my heart at the time I am composing,” he once told an interviewer. “If there is love there, or bitterness, or sadness, or religion, these moods become part of my music, and it becomes either beautiful or bitter or sad or religious.”

It is nostalgic sadness that permeates the works of Rachmaninoff’s later years. Like a grim marker, the ancient chant Dies Irae (“Day of Wrath”) from the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass for the Dead courses through the Paganini Rhapsody (1934), the Second (1908) and Third (1936) Symphonies, and the Symphonic Dances (1940). The Symphonic Dances were his last important creation, coming less than three years before his death from cancer at age 70, but there is nothing morbid about them. They breathe a spirit of dark determination against a world of trial, a hard-fought musical affirmation of the underlying resiliency of life. Received with little enthusiasm when they were new, these Dances have come to be regarded as among the finest of Rachmaninoff’s works.

The first of the Symphonic Dances, in a large three-part form (A–B–A), is spun from a tiny three-note descending motive heard at the beginning that serves as the germ for much of the opening section’s thematic material. The middle portion is given over to a folk-like melody initiated by the alto saxophone. The return of the opening section, with its distinctive falling motive, rounds out the first movement. The waltz of the second movement is more rugged and deeply expressive than the Viennese variety and possesses the quality of pathos that gives so much of Rachmaninoff’s music its sharply defined personality. The finale begins with a sighing introduction for the winds, which leads into a section in quicker tempo whose vital rhythms may have been influenced by the syncopations of American jazz. Soon after this faster section begins, the chimes play a pattern reminiscent of the opening phrase of the Dies Irae. The sighing measures recur and are considerably extended, acquiring new thematic material but remaining unaltered in mood. When the fast, jazz-inspired music returns, its thematic relationship with the Dies Irae is strengthened. The movement accumulates an almost visceral rhythmic energy as it progresses, exploding into the last pages, a coda based on an ancient Russian Orthodox chant (which he had earlier used in his All-Night Vigil Service of 1915) whose entry Rachmaninoff noted by inscribing “Alliluya” in the score.

Was a specific message intended here? As the Alliluya succeeds the Dies Irae, did the composer mean to show that the Church conquers death? Optimism, sadness? Rachmaninoff was silent on the matter, except to say, “A composer always has his own ideas of his works, but I do not believe he ever should reveal them. Each listener should find his own meaning in the music.”

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, glockenspiel, xylophone, chimes, tambourine, triangle, tam-tam and the usual strings.