30 SECOND NOTES: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, born in London of a white English woman and a physician from Sierra Leone, was a leading British composer of his generation as well as a highly respected figure in America, where his works were compared to Mahler and Dvořák during his 1910 visit to New York City. Coleridge-Taylor wrote several important works inspired by Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha, including an overture to precede a triptych of large cantatas based on the epic poem. Joseph Haydn composed prolifically for orchestra, chamber ensembles, opera and vocalists during the three decades he served the Esterházy family, all of it for immediate use by the court’s professional musicians or, occasionally, a member of the noble family. The Cello Concerto in D Major was written for Anton Kraft, a talented performer who was a colleague of Haydn for many years. Antonín Dvořak’s beloved New World Symphony, written in 1892 when he was directing the new National Conservatory in New York City, was inspired by the plantation spirituals he learned from a Black scholarship student.

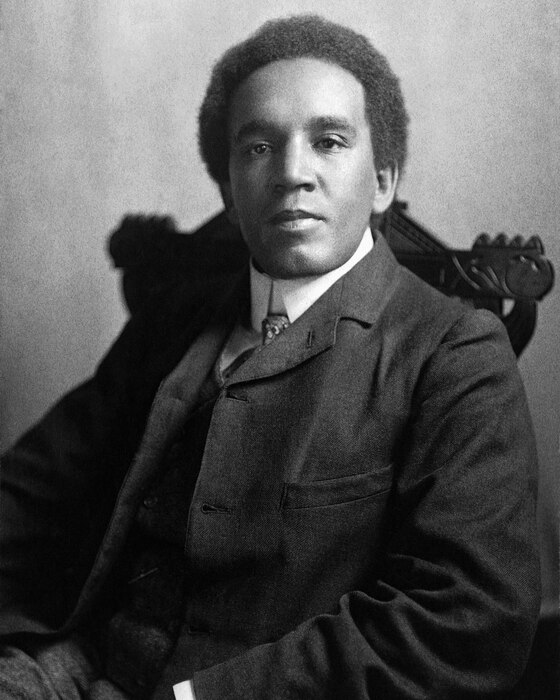

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

- Born August 15, 1875 in London;

- died September 1, 1912 in Croydon.

OVERTURE TO THE SONG OF HIAWATHA, OP. 30, NO. 3

- First performed on October 6, 1899 at the Triennial Music Festival in Norwich, England, conducted by the composer.

- These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 12 minutes)

Though Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was English by birth, training and residence, he was unquestionably a hero to American audiences. Born in London in 1875 to a white English woman and a physician from Sierra Leone, Samuel was brought up in suburban Croydon by his mother after his father returned to Africa to practice medicine. As a boy, Coleridge-Taylor studied violin with a local teacher, sang in a church choir, and showed talent as a composer, and in 1890, he was admitted to the Royal College of Music. By the time he graduated in 1897, he had produced a significant collection of works, including a symphony and several large chamber compositions, a number of which were performed publicly. His music became known to Edward Elgar, who offered the young musician advice and encouragement. Coleridge-Taylor’s greatest success came in 1898 with the premiere of the cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, the first of several works inspired by the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He held a number of conducting and teaching positions thereafter in London, including appointments as professor of composition at the Trinity College of Music and Guildhall School of Music. Coleridge-Taylor composed steadily throughout his life and became one of the most respected musicians of his generation on both sides of the Atlantic — New York orchestral players compared his works to those of Mahler and Dvořák during his visit to the city in 1910. His premature death from pneumonia at the age of 37 in 1912 seems to have been partly a result of overwork.

Coleridge-Taylor’s music found great favor in the United States during his lifetime. Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast had been performed twice in Boston by 1900, and his music was espoused by the famous African-American baritone Henry Burleigh, whose songs were an important inspiration for Dvořák’s New World Symphony. Coleridge-Taylor’s visits to this country in 1904, 1906 and 1910 were sponsored by the Coleridge-Taylor Society, founded in 1901 in Washington, D.C. to study and perform his music and to encourage African-American musicians. President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to the White House after a performance of Hiawatha in 1904. Coleridge-Taylor was strongly drawn to America and its African-American culture, and he was considering moving here at the time of his death.

The writings of Longfellow exercised a fascination on Coleridge-Taylor throughout his life. In addition to the three large cantatas for chorus and orchestra comprising the complete Scenes from “The Song of Hiawatha” (Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, The Death of Minnehaha and Hiawatha’s Departure, plus an overture to preface the entire cycle), he wrote the Hiawathan Sketches for Violin and Piano, set several of Longfellow’s Poems of Slavery for chorus, and wrote short ballets titled Hiawatha and Minnehaha that were his last completed works. (Coleridge-Taylor named his son, born in 1900, Hiawatha.) The Overture to The Song of Hiawatha was composed in 1899, when Coleridge-Taylor was at work on The Death of Minnehaha, the cycle’s second cantata; it was premiered under this direction at the Triennial Musical Festival at Norwich Cathedral on October 6, 1899 to preface the performance of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. The Overture was played again three weeks later at the premiere of The Death of Minnehaha.

The Overture to The Song of Hiawatha, which evidences Coleridge-Taylor’s gifts for both lyricism and drama, is built in a well-crafted sonata form with slow introduction whose poignant main theme recalls the spiritual Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen; the expressive second theme is introduced by horns, clarinets, violas and cellos. The Overture closes with a short, affirmative coda based on a choral episode from Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, harp and the usual strings.

JOSEPH HAYDN

- Born March 31, 1732 in Rohrau, Austria;

- died May 31, 1809 in Vienna.

CELLO CONCERTO IN D MAJOR

- Possibly first performed in Vienna on September 15.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on November 20, 1949 conducted by Frank Noyes with Pierre Fournier as soloist. One subsequent performance occurred on January 15, 1953 conducted by Frank Noyes with John Ehrlich as soloist.

(Duration: ca. 25 minutes)

Haydn wrote the Cello Concerto in D Major in 1783, perhaps for the festivities surrounding the wedding of Prince Nicolaus Esterházy and Princess Josepha Hermangild Liechtenstein in Vienna on September 15th. It is one of some half-dozen concerted works for cello that he composed between 1771 and 1783, of which only this and the delightful Concerto in C Major survive. The Concerto in D Major exhibits some aspects of writing for the solo instrument that were unusual for the time. The consistently high tessitura and treacherous double-stops, for example, were little used in the late 18th century, and they serve as testimony to the excellent skill of Anton Kraft, a talented cellist who performed for many years in Haydn’s orchestra at Esterháza, for whom the work was written. More gallant than deeply emotional in its musical language, this Concerto is enjoyable and entertaining as well as being a dazzling showpiece for the virtuoso performer.

The Concerto’s stylish first movement moves with a noble, unhurried gait. An orchestral introduction presents the stately main theme before it is taken over and embellished by the soloist. A complementary second theme is introduced by the cello. The development section is filled with nimble figuration. The second movement is an extended song for the soloist played over a graceful, rocking accompaniment. The finale is a rondo based on a bounding tune presented immediately by the soloist.

This score calls for two oboes, two horns and the usual strings.

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

- Born September 8, 1841 in Nelahozeves, Bohemia;

- died May 1, 1904 in Prague.

SYMPHONY NO. 9 IN E MINOR, OP. 95, "FROM THE NEW WORLD"

- First performed on December 16, 1893 at Carnegie Hall by the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Anton Seidl.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on March 12, 1950 with Frank Noyes conducting. Four subsequent performances occurred, most recently on March 16 & 17, 2019 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 42 minutes)

There would not have been a New World Symphony without Mrs. Jeanette Thurber, one of America’s most ardent and effective supporters of the arts during the decades around the turn of the 20th century. The daughter of a Danish immigrant violinist, she was born Jeanette Meyers in 1850 in a small town 150 miles north of New York City, immersed in music as a child, and trained in the field at the venerable Paris Conservatoire, whose support by the national government became the model she sought to duplicate at home. Aided by the fortune of her husband, Francis Beatty Thurber, a wealthy grocery wholesaler, she obtained a state charter in 1885 to establish a National Conservatory of Music in New York City, which she intended not just as a school for training the country’s most talented musicians, but also as a radically progressive social institution, admitting women, Blacks, Native Americans and handicapped students on an equal basis. In 1891, the school was incorporated by a special act of Congress and authorized to grant diplomas and confer honorary degrees.

To direct the National Conservatory, Mrs. Thurber turned in 1892 to a composer and educator of international renown — Antonín Dvořák, who was already well-known in New York through his chamber and piano compositions (the Slavonic Dances of 1878 and 1886 were an international hit) as well as the symphonies and shorter orchestral works that the New York Philharmonic had programmed a dozen times during the previous decade. As an emissary to Dvořák, Mrs. Thurber dispatched the Vienna-born pianist Adele Margolies, a Conservatory faculty member, to Prague. Dvořák was at first reluctant to leave his beloved Czech homeland, but when Mrs. Thurber’s offer ballooned to a breathtaking $15,000 per annum (some $500,000 today and several multiples of Dvořák’s salary at the Prague Conservatory) and the expenses for resettling his family included, he agreed to a term of three years. His responsibilities were also arranged to allow sufficient time for his own creative work — four months’ summer leave, three hours of daily teaching, and involvement in six annual concerts. Soon after arriving in New York in September 1892, Dvořák wrote to a friend in Prague, “The Americans expect great things of me and the main thing is, so they say, to show them to the promised land and kingdom of a new and independent art, in short, to create a national music…. There is more than enough material here and plenty of talent.” Despite Mrs. Thurber’s dedicated efforts to sustain the National Conservatory, its spending outstripped available resources, government funding never materialized, and competition from the Institute of Musical Art of New York, established in 1904 (and which became the Juilliard School in 1926), forced her institution to close in 1928. The New World Symphony that she and her school inspired from its most famous faculty member remains a permanent part of that legacy.

It was precisely Mrs. Thurber’s liberal admission policies that motivated the New World Symphony in the person of Henry Thacker Burleigh, a gifted Black singer, pianist and songwriter from Erie, Pennsylvania who won a scholarship to the National Conservatory in 1892 and became a student of Dvořák. Burleigh sang many of the traditional melodies for his teacher, who recognized in them some similarities in expression and construction to the folk music of his Czech homeland. “Dr. Dvořák was very deeply impressed by the Negro spirituals from the old plantation,” Burleigh recalled. “He just saturated himself in the spirit of those old tunes.” Dvořák’s response appeared in the New York Herald: “The Negro melodies of America can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States.... There is nothing in the whole range of composition that cannot find a thematic source here.”

Inspired by Henry Burleigh’s songs, heritage and personality (Burleigh went on to a distinguished career as soloist at New York’s St. George’s Episcopal Church and Temple Emanu-El, nationally known baritone recitalist, composer of 300 songs, and charter member of ASCAP), Dvořák began the Symphony “From the New World” in December 1892 and completed it in May (its sobriquet may have been suggested by Mrs. Thurber). “I should never have written the Symphony as I have,” he said, “if I hadn’t seen America.” The work triumphed at its premiere, given on December 16, 1893 in Carnegie Hall by conductor Anton Seidl and the New York Philharmonic, and immediately earned a place in the orchestral repertory that has never waned.

The New World Symphony is unified by the use of a motto theme that occurs in all four movements. This bold, striding phrase, with its arching contour, is played by the horns as the main theme of the sonata-form opening movement, having been foreshadowed (also by the horns) in the slow introduction. Two other themes are used in the first movement: a sad, dance-like melody for flute and oboe that exhibits folk characteristics, and a brighter tune, with a striking resemblance to the spiritual Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, for the solo flute.

Many years before coming to America, Dvořák had encountered Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, which he read in a Czech translation. The great tale remained in his mind, and he considered making an opera of it during his time in New York. That project came to nothing, but Hiawatha did have an influence on the New World Symphony: the second movement was inspired by the forest funeral of Minnehaha; the third, by the dance of the Indians at the feast.

The second movement is a three-part form (A–B–A), with a haunting English horn melody (later fitted with words by William Arms Fisher to become the folksong-spiritual Goin’ Home) heard in the first and last sections. The recurring motto here is pronounced by the trombones just before the return of the main theme in the closing section. The third movement is a tempestuous scherzo with two gentle, intervening trios providing contrast. The motto theme, played by the horns, dominates the coda.

The finale employs a sturdy motive introduced by the horns and trumpets after a few introductory measures in the strings. In the Symphony’s closing pages, the motto theme, Goin’ Home and the scherzo melody are all gathered up and combined with the principal subject of the finale to produce a marvelous synthesis of the entire work — a look back across the sweeping vista of Dvořák’s musical tribute to America.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals and the usual strings.