30 SECOND NOTES: Die Meistersinger by Richard Wagner, a masterwork of German operatic art, is about many things, but it is at heart a love story of a young couple brought together through music. It is magnificently scored and richly melodic, and several of its most important themes are woven into the stirring Prelude. Though Johannes Brahms was raised in the beliefs of German Protestantism, he was not a religious man. He did, however, have high regard for sacred traditions, texts and beliefs, and in mid-1860s, upon the death of his mother, he composed A German Requiem on Biblical verses. Brahms’ Nänie of 1881, on a poem with classical references by Schiller, is a secular counterpart to the great German Requiem. Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana has become a popular icon, supercharging TV commercials, on-field performances of The Ohio State University Marching Band and the entry of the home teams on some NBA courts (with, occasionally, accompanying flamethrowers), but it remains music of elemental power that is one of the concert hall’s most thrilling experiences.

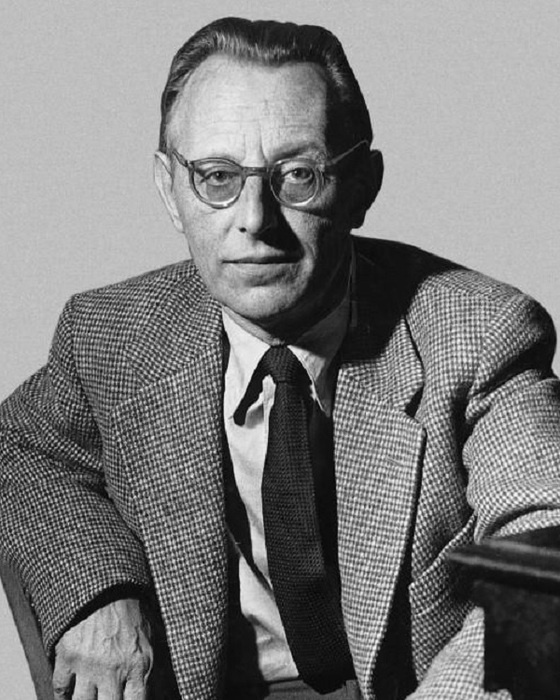

RICHARD WAGNER

- Born May 22, 1813 in Leipzig;

- died Februrary 13, 1883 in Venice.

PRELUDE TO MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG ("THE MASTERSINGERS OF NUREMBERG")

- First performed in June 21,1868 in Munich, conducted by Hans von Bülow.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on May 1, 1938 with Frank Noyes conducting. Nine subsequent performances occurred, most recently on November 17 & 18, 2018 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 10 minutes)

The plot of Die Meistersinger centers around a song contest held in 16th-century Nuremberg on St. John’s Day (June 24). The winner is to marry Eva, daughter of the goldsmith Veit Pogner. Walther von Stolzing, a young knight from Franconia in love with Eva, vows to win the contest and her hand, even though he is not a member of the guild of Mastersingers. He is granted permission to compete despite the attempts of Sixtus Beckmesser, the town clerk and also a contestant, to discredit him for not knowing the ancient guild rules governing the composition of a song. Eva and Walther communicate their love to the wise cobbler Hans Sachs, who remains their friend and adviser despite his own love for the girl. Sachs helps Walther shape his musical and poetic ideas, which bring a new freshness and expression to the staid ways of the guild. Beckmesser, having stolen Walther’s poem, gives it a ludicrous musical setting, and makes a fool of himself at the contest. Sachs invites Walther to show how the verses should be sung, and the young knight is acclaimed the winner.

The Prelude, written between March and June 1862, was the first part of the score to be completed, and served as the thematic source for much of the opera. It opens with the majestic processional of the Mastersingers intoned by the full orchestra. A tender theme portraying the love of Eva and Walther leads to a second Mastersinger melody, this one said to have been based on The Crowned Tone by the 17th-century guild member Heinrich Mögling. The Prelude’s first section closes with the development of another love motive and phrases later heard in Walther’s Prize Song. The central portion is largely devoted to a cackling, fugato parody of the first Mastersinger theme that anticipates Beckmesser’s buffooneries. The Prelude is brought to a magnificent ending with a masterful weaving together of all its themes.

Score written for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle, harp and the usual strings.

JOHANNES BRAHMS

- Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg;

- died April 20, 1897 in Vienna.

NÄNIE FOR CHORUS AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 82

- First performed on December 12, 1881 in Zurich, conducted by the composer.

- These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 13 minutes)

Nänie, the title of this solemnly beautiful work, is a German term derived from the Latin word for “dirge.” This musical tribute was Brahms’ commemoration of the death of his close friend, artist Anselm Feuerbach, in January 1880. While still feeling the pain of that recent loss, Brahms attended a performance on February 14, 1880 at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde that included a setting of Schiller’s poem Nänie by the German composer Hermann Goetz (1840-1876). The comforting serenity engendered the poem was a balm for Brahms’ own sorrow, and he was inspired by it to create his own musical memorial to his late friend.

Walter Niemann, Brahms’ biographer, described the background of the text: “Neniae were the laments [of the ancient Greeks] for the dead sung at their funerals, originally by the surviving relatives, but later by hired female mourners, who beat their breasts and arms in sign of grief as they sang.... [In Brahms’ setting of Schiller’s poem,] Death is represented as a kindly young divinity, the twin brother of Sleep. Softly he extinguishes the flame of life.” Brahms’ music throughout is peaceful and reassuring, recalling the opening and closing movements of his German Requiem. He cast the work in three-part form, with the placid opening section returning at the end. The central portion (“Aber sie steigt aus dem Meer”) becomes more active to depict Aphrodite’s rising from the sea. Brahms closed this memorial tribute with the consoling phrase, “To be even a song of lament on the lips of the loved one, is glory.”

Score written for woodwinds in pairs, two horns, three trombones, timpani, harp and the usual strings.

CARL ORFF

- Born July 10, 1985 in Munich;

- died March 29, 1982 in Munich.

CARMINA BURANA

- First performed on December 8, 1937 in Frankfurt, conducted by Bertil Wetzberger.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on May 18, 1969 with Robert Gutter conducting. Two subsequent performances occurred, most recently on April 13 & 14, 2013 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 60 minutes)

About thirty miles south of Munich, in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps, is the abbey of Benediktbeuren. In 1803, a 13th-century codex was discovered among its holdings that contains some 200 secular poems which give a vivid, earthy portrait of Medieval life. Many of these poems, attacking the defects of the Church, satirizing contemporary manners and morals, criticizing the omnipotence of money, and praising the sensual joys of food, drink and physical love, were written by an amorphous band known as “Goliards.” These wandering scholars and ecclesiastics, who were often esteemed teachers and recipients of courtly patronage, filled their worldly verses with images of self-indulgence that were probably as much literary convention as biographical fact. The language they used was a heady mixture of Latin, old German and old French. Some paleographic musical notation appended to a few of the poems indicates that they were sung, but it is today so obscure as to be indecipherable. This manuscript was published in 1847 by Johann Andreas Schmeller under the title Carmina Burana (“Songs of Beuren”), “carmina” being the plural of the Latin word for song, “carmen.”

Carl Orff encountered these lusty lyrics for the first time in the 1930s, and he was immediately struck by their theatrical potential. Like Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson in the United States, Orff at that time was searching for a simpler, more direct musical expression that could immediately affect listeners. Orff’s view, however, was more Teutonically philosophical than that of the Americans, who were seeking a music for the common man, one related to the everyday world. Orff sought to create a musical idiom that would serve as a means of drawing listeners away from their daily experiences and closer to the realization of oneness with the universe. In the words of the composer’s biographer Andreas Liess, “Orff’s spiritual form is molded by the superimposition of a high intellect on a primitive creative instinct,” thus establishing a tension between the rational (intellect) and the irrational (instinct). The artistic presentation of the deep-seated psychological self to the thinking person allows an exploration of the regions of being that have been overlaid by accumulated layers of civilization. To portray the connection between the physical and spiritual spheres, Orff turned to the theater. His theater, however, was hardly the conventional one. Orff’s modern vision entailed stripping away not only the richly Romantic musical language of traditional opera, but also eliminating its elaborate stagecraft, costumes and scenery so that it was reduced to just its essential elements of production. Orff’s reform even went so far as to question the validity of any works written before 1935, including his own, to express the state of modern man, and he told his publisher to destroy all his music (i.e., Orff’s) that “unfortunately” had been printed. The first piece that embodied Orff’s new outlook was Carmina Burana.

Though Carmina Burana is most frequently heard in the concert hall, Orff insisted that it was intended to be staged, and that the music was only one of its constituent parts. “I have never been concerned with music as such, but rather with music as ‘spiritual discussion,’” he wrote. “Music is the servant of the word, trying not to disturb, but to emphasize and underline.” He felt that this objective was best achieved in the theater, but Carmina Burana still has a stunning impact even without its visual element. Its effect arises from the monumental simplicity of the musical style by which Orff sought to depict the primitive, instinctive side of mankind. Gone are the long, intricate forms of traditional German symphonic music, the opulent homogeneity of the Romantic orchestra, the rich textures of the 19th-century masters. They are replaced by a structural simplicity and a sinewy, dynamic muscularity that is driven by an almost primeval rhythmic energy. “The simpler and more reduced to essentials a statement is, the more immediate and profound its effect,” wrote Orff.

It is precisely through this enforced simplicity that Orff intended to draw listeners to their instinctual awareness of “oneness with the universe.” Whether he succeeded as philosopher is debatable. Hanspeter Krellmann wrote in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, “The four aspects of Orff’s musical theater [tragedy of archetypes, visionary embodiment of metaphysical ideas, bizarre fantasy and physical exuberance] are usually intertwined; and it is apparent from the works that Orff’s main concern is not with the exposition of human nature in tragedy, nor with whimsical fancy, nor with the statement of supernatural truths, nor with joyous exultation. His intention seems to be to create a spectacle.”

So what then is Carmina Burana: a set of ribald songs? a Medieval morality play? a philosophical tract? Perhaps it is all of these. But more than anything, it is one of the most invigorating, entertaining, easily heard and memorable musical creations of the 20th century.

Orff chose 24 poems from the Carmina Burana to include in his work. Since the 13th-century music for them was unknown, all of their settings are original with him. The work is disposed in three large sections with prologue and epilogue. The three principal divisions — Primo Vere (“Springtime”), In Taberna (“In the Tavern”) and Cour d’Amours (“Court of Love”) — sing the libidinous songs of youth, joy and love. However, the prologue and epilogue (using the same verses and music) that frame these pleasurable accounts warn against unbridled enjoyment. “The wheel of fortune turns; dishonored I fall from grace and another is raised on high,” caution the words of Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (“Fortune, Empress of the World”), the chorus that stands like pillars of eternal verity at the entrance and exit of this Medieval world. They are the ancient poet’s reminder that mortality is the human lot, that the turning of the same Wheel of Fortune that brings sensual pleasure may also grind that joy to dust. It is this bald juxtaposition of antitheses — the most rustic human pleasures with the sternest of cosmic admonitions — coupled with Orff’s elemental musical idiom that gives Carmina Burana its dynamic theatricality.

The work opens with the chorus Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi, depicting the terrible revolution of the Wheel of Fate through a powerful repeated rhythmic figure that grows inexorably to a stunning climax. After a brief morality tale (Fortune plango vulnera — “I lament the wounds that fortune deals”), the Springtime section begins. Its songs and dances are filled with the sylvan brightness and optimistic expectancy appropriate to the annual rebirth of the earth and the spirit. The next section, In Taberna (“In the Tavern”), is given over wholly to the men’s voices. Along with a hearty drinking song are heard two satirical stories: Olim lacus colueram (“Once in lakes I made my home”) — one of the most difficult pieces in the tenor repertory — and Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis (“I am the abbot of Cucany”). The third division, Cour d’Amours (“Court of Love”), leaves far behind the rowdy revels of the tavern to enter a refined, seductive world of sensual pleasure. The music is limpid, gentle and enticing, and marks the first appearance of the soprano soloist. The lovers’ urgent entreaties grow in ardor, with insistent encouragement from the chorus, until submission is won in the most rapturous moment in the score, Dulcissime (“Sweetest Boy”). The grand paean to the loving couple (Blanzifor et Helena) is cut short by the intervention of imperious fate, as the opening chorus (Fortuna), like the turning of the Great Wheel, comes around once again to close this mighty work.

Karl Schumann wrote of the universality of Orff’s Carmina Burana, “No individual destiny is touched upon — there are no dramatic personae in the normal sense of the term. Instead, primeval forces are invoked, such as the ever-turning Wheel of Fortune, the revivifying power of spring, the intoxicating effect of love, and those elements in man that prompt him to the enjoyment of earthly and all-too-earthly pleasures. The principal figure is man, as a natural being delivered over to forces stronger than himself.”

Scored for two piccolos, three flutes, three oboes, English horn, E-flat clarinet, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, three glockenspiels, xylophone, chimes, tambourine, triangle, castanets, ratchet, sleigh bells, tam-tam, celesta, two pianos and the usual strings.