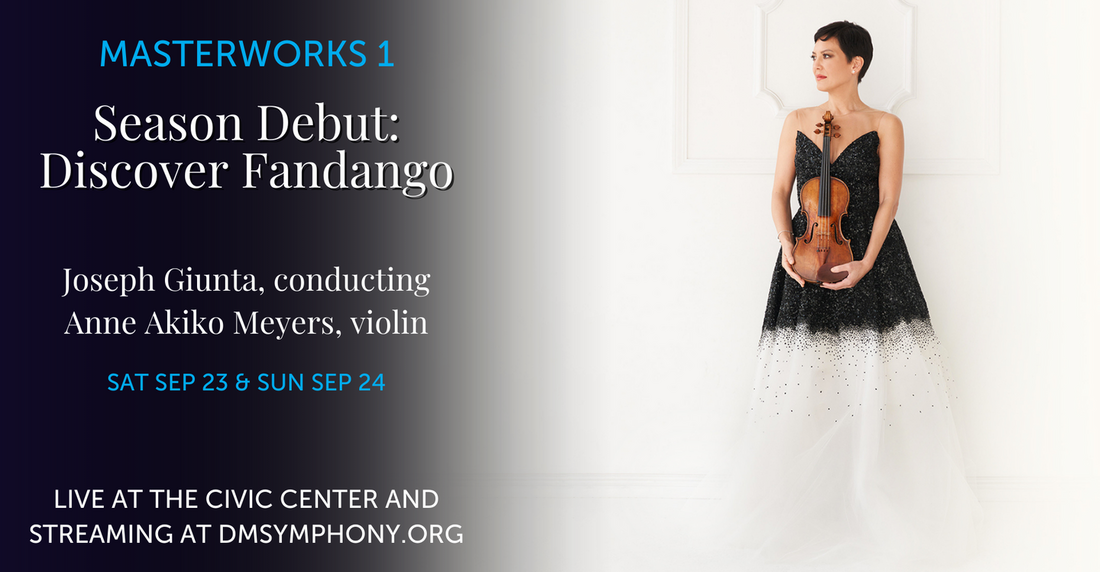

The 2023-2024 Des Moines Symphony season debut offers views of Latin music culture from home and abroad. The French composer Emmanuel Chabrier visited Spain in 1882 and assembled his impressions into the colorful España (which some listeners will recognize as the source of Perry Como’s 1950s hit Hot Diggity). Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio espagnol was a souvenir of that Russian composer’s only visit to Spain two decades before as a naval cadet. The soulful Danzón No. 6 and the brilliant violin concerto Fandango, written in 2020 for Anne Akiko Meyers, on the other hand, were drawn directly from Mexican musical sources by Arturo Márquez, one of his country’s preeminent musicians.

EMMANUEL CHABRIER

Born January 18, 1841 in Ambert, Puy de Dôme, France;

died September 13, 1894 in Paris.

ESPAÑA

• First performed on November 4, 1883 in Paris, conducted by Charles Lamoureux.

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on March 16, 1947 with Frank Noyes conducting. Five subsequent performances occurred, most recently on January 30 & 31, 2010 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 7 minutes)

“Every night finds us at the bailos flamencos [sic], surrounded by toreros in lounge suits, black felt hats cleft down the middle, jackets nipped in at the waist and tight trousers revealing sinewy legs and finely modeled thighs. And all around, the Gypsy women singing their malaguenas or dancing the tango.” Thus ran an excited report from the French composer Emmanuel Chabrier to some Parisian friends concerning his trip to Spain in 1882. Chabrier transcribed Spain’s indigenous music at every stop, and he told the conductor Charles Lamoureux, director of the Société des Nouveaux Concerts in Paris, that he planned to write a new work on the themes he collected, “... una fantasia extraordinaria, muy española ... my rhythms, my tunes will arouse the whole audience to a fever pitch of excitement; everyone will embrace his neighbor madly.” Chabrier set to work on España as soon as he arrived home in December. He played the original piano version early the next year for Lamoureux, who was so impressed that he encouraged the composer to orchestrate the piece so that it could be programmed at the Nouveaux Concerts later that season. España created a sensation when it premiered in November 1883 — it was Chabrier’s first unqualified success and overnight established him among the leading creative figures of French music.

Chabrier noted that the chief characteristic of España is the manner in which it juxtaposes and blends the fierce, rough strains of the jota with the sensuous, dreamy undulations of the malagueña, both sections based on songs he had collected in Spain. To these motives, he added a melody of his own invention, first intoned by the trombones in the work’s middle section.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, four bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, two cornets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle,two harps and the usual strings consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

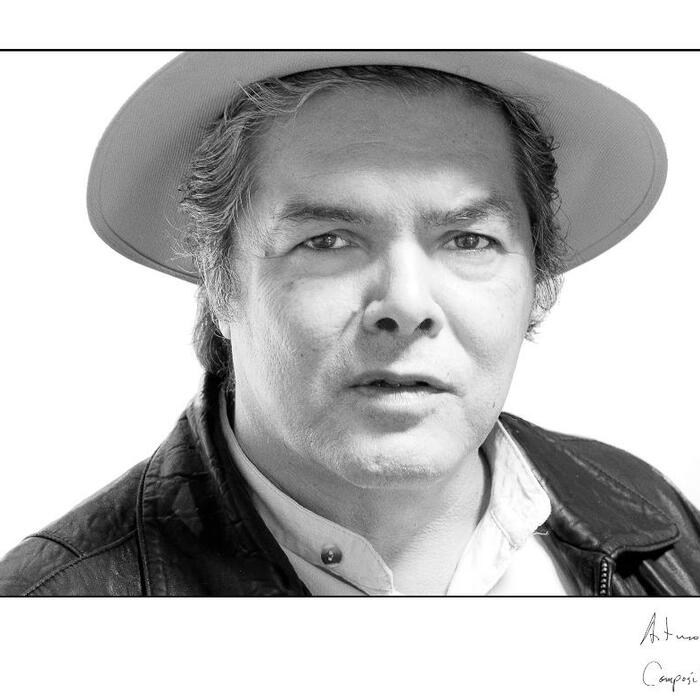

ARTURO MÁRQUEZ

Born December 20, 1950, in Alamos Sonora, Mexico.

DANZÓN NO. 6 FOR SOPRANO SAXOPHONE & STRING ORCHESTRA, “PUERTO CALVARIO”

• First performed on June 24, 2001 in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico by the State Symphony Orchestra of Xalapa.

• These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 7 minutes)

Arturo Márquez was born in 1950 in Alamos, in the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora, where his father was a mariachi violinist. Arturo Sr. introduced his son to music and when the family moved to Los Angeles in 1962, young Arturo was ready to begin studying violin and immersing himself in a variety of musical styles — “I spent my adolescence,” he recalled, “listening to [Mexican singer] Javier Solis, sounds of mariachi, the Beatles, Doors, Carlos Santana and Chopin.” By the time the family returned to Sonora when he was seventeen, he had started to compose and was ready to become director of the municipal band in Navojoa the following year. Márquez went to Mexico City in 1970 to begin his professional studies at the Conservatorio Nacional de Música, where he majored in piano and composition. From 1976 to 1979, he studied at the Institute of Fine Arts of Mexico with Joaquín Gutiérrez Heras, Hector Quintanar and Federico Ibarra, and a French government grant in 1980 enabled him to study in Paris with Jacques Castérède for two years; he did his academic graduate work on a Fulbright scholarship at the California Institute of the Arts with Morton Subotnick, Stephen Mosko, Mel Powell and James Newton. Arturo Márquez, today one of Mexico’s most respected musicians, has taught at the National University of Mexico, held a residency at the National Center of Research, Documentation and Information of Mexican Music, fulfilled commissions from the Organization of American States, Universidad Metropolitana de México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Festival del Caribe, Festival de la Ciudad de México, 1992 Seville World’s Fair and Rockefeller Foundation, and received, among many distinctions, Mexico’s National Prize for Arts and Sciences, Austrian Embassy’s Medalla Mozart, and Gold Medal of Fine Arts of Mexico, the first musician honored with the country’s highest award for artists.

Márquez has composed nine works for varied instrumentation titled Danzón. In 1942, after a goodwill visit to Cuba, Aaron Copland wrote his Danzón Cubano and gave the following description of the form: “The popular dance style known as danzón has a very special character. It is a stately dance, quite different from the rhumba, conga and tango, and one that fulfills a function rather similar to that of the waltz in our own music, providing contrast to some of the more animated dances. The danzón is not the familiar hectic, flashy and rhythmically complicated type of Cuban dance. It is more elegant and curt and is very precise, as dance music goes. The dance itself seemed especially amusing to me because it has a touch of unconscious grotesquerie, as if it were an impression of ‘high-life’ as seen through the eyes of the populace — elegance perceived by the inelegant.”

Marquez composed his Danzón No. 6 for a concert at the inaugural International University Book Fair at the University of Veracruz in Xalapa, which opened on June 24, 2001 with a session honoring the composer with the State Symphony of Veracruz performing several of his works. Marquez wrote of the Danzón No. 6, scored for soprano saxophone and string orchestra that utilizes both the soulful voice and the agility of the soloist, “I discovered that the apparent lightness of the danzón hides a music full of sensuality and rigor, music of nostalgia and joy that our old folks live with, a world that we can still grasp in the dance music of Veracruz and the dance halls of Mexico City.”

The score calls for the usual strings and solo soprano saxophone.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Born March 18, 1844 in Tikhvin, near Novgorod;

died June 21, 1908 in St. Petersburg.

CAPRICCIO ESPAGNOL, OP. 34

• First performed on October 31, 1887 in St. Petersburg, conducted by the composer.

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on January 15, 1950 with Frank Noyes conducting. Five subsequent performances occurred, most recently on October 17 & 18, 2015 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 16 minutes)

Rimsky-Korsakov visited Spain only once: while on a training cruise around the world as a naval cadet, he spent three days in the Mediterranean port of Cádiz in December 1864. The sun and sweet scents of Iberia left a lasting impression on him, however, just as they had on the earlier Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, who was inspired to compose his Jota Aragonesa and A Night in Madrid on Spanish themes. Both of those colorful works by his Russian predecessor were strong influences on Rimsky-Korsakov when he came to compose his own Spanish piece in 1887.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s principal project during the summer of 1887 was the orchestration of the opera Prince Igor by his compatriot Alexander Borodin, who had died the preceding winter. Rimsky installed himself at Nikolskoe on the shore of Lake Nelai in a rented villa, and made good progress with the opera, one of many completions and revisions he undertook of the music of his fellow Russian composers. Things went well enough that he felt able to interrupt this project for several weeks to work on his piece on Spanish themes, originally intended for solo violin and orchestra but which he re-cast for full orchestra as the brilliant Capriccio espagnol.

The Capriccio espagnol comprises five brief, attached movements. It opens with a rousing Alborada or “morning song,” marked vivo e strepitoso — “lively and noisy.” The solo violin figures prominently here and throughout the work, a reminder of the virtuosic origin of the Capriccio as a concerted piece for that instrument. A tiny set of variations on a languid theme presented by the horns follows. The Alborada returns in new instrumental coloring that features a sparkling solo by the clarinet. The fourth movement, Scena e canto gitano (“Scene and Gypsy Song”), begins with a string of cadenzas: horns and trumpets, violin, flute, clarinet and harp. The swaying Gypsy Song gathers up the instruments of the orchestra to build to a dazzling climax leading without pause to the finale, Fandango asturiano. The trombones present the theme of this section, based on the rhythm of a traditional dance of Andalusia. The final pages of the Capriccio recall the Alborada theme to bring this brilliant orchestral showpiece to an exhilarating close.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, castanets, harp and the usual strings.

Arturo Márquez

FANDANGO FOR VIOLIN & ORCHESTRA

• First performed on August 24, 2021, at the Hollywood Bowl by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel with Anne Akiko Meyers as soloist.

• These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 34 minutes)

Arturo Márquez wrote of his Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, “The Fandango is known worldwide as a popular Spanish dance and, specifically, as one of the fundamental parts (Palos) of flamenco. Since its appearance around the 18th century, such composers as de Murcia, Domenico Scarlatti, Boccherini, Padre Soler, Mozart and others have included Fandango in concert music. Soon after its appearance in Spain, the Fandango moved to the Americas, where it acquired a personality adapted to the local cultures. It is still found in Ecuador, Colombia and Mexico, specifically in the state of Veracruz and the Huasteca area in eastern Mexico, where it accompanies a special festival for musicians, singers, poets and dancers in which everyone gathers around a wooden platform to stamp their feet, sing and improvise ten-line stanzas appropriate for the occasion. It should be noted that Fandango and Huapango have similar meanings in Mexico.

“In 2018, I received an email from violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, a wonderful musician, in which she proposed writing a work for violin and orchestra rooted in Mexican music. The proposal interested me immediately, not just because of my admiration for her musicality and virtuosity but, above all, for her courage in proposing a concerto so out of the ordinary. I had already tried, unsuccessfully, to compose a violin concerto some twenty years earlier with ideas based on the Mexican Fandango. I have known this music since I was a child, listening to it in the cinema and on the radio, and hearing my father, a mariachi violinist (Arturo Márquez, Sr.), interpret Huastecos and mariachi music. I would like to mention that the violin was my first instrument — when I was fourteen I studied it in La Puente, California in Los Angeles County, in which same county, fortuitously, this Concerto was premiered by Ms. Meyers, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel in August 2021. It was a beautiful coincidence that Fandango connects 18th-century California with the present day.

“The first movement, Folia Tropical, has the form of the traditional classical concerto: introduction, exposition with two themes, bridge, development and recapitulation. The introduction and the two themes share the same motif but use it in a totally different way. Emotionally, the introduction is a call to the remote history of the Fandango; the first theme and the bridge are based on the Caribbean ‘Clave’ rhythm; the second is eminently expressive, almost like a romantic Boléro. Folias are ancient dances from Portugal and Spain whose title was borrowed from the French word ‘Folie’: madness.

“The second movement, Plegaria(‘Prayer’), pays tribute to the Huapango mariachi together with the Spanish Fandango in both its rhythmic and emotional aspects. I do not use traditional themes but there is an attempt to unite both worlds, an imaginary marriage between the Huapango–Mariachi and the concert music of Pablo Sarasate, Manuel de Falla and Issac Albéniz, three of my beloved and admired Spanish composers. The movement is also a freely treated Chaconne, (i.e., based on a repeating pattern), evolved from a late-16th- and early-17th-century dance forbidden by the Spanish Inquisition before it became part of European Baroque music. This dance was also known in colonial Mexico at that time.

“The third movement, Fandanguito, is a tribute to the Fandangito Huasteco, music for violin, jarana huasteca (small rhythm guitar) and huapanguera (low guitar with five orders of strings) that accompanies singing of sones and improvised song or recitation. The Huasteco violin is one of the most virtuosic instruments in all of America. It has certain features similar to Baroque practice but with great rhythmic vitality and a rich original variety in bow strokes. This movement reflects that virtuosity. It is a free elaboration of the Huasteco Fandanguito, but maintains many of its rhythmic characteristics. It is music I have kept in my heart for decades.

“I think that for every composer it is a real challenge to compose new works from old forms, especially when that repertoire is part of the fundamental canon of classical music. On the other hand, composing this work during the 2020 pandemic was not easy due to the huge human suffering. Undoubtedly my experience with this work during that period was intense and highly emotional, but I have preserved my seven stylistic principles: tonality, modality, melody, rhythm, imaginary folk tradition, harmony and orchestral color.”

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two bassoons, four horns, three trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, claves, guiro, cajon, harp and the usual strings.