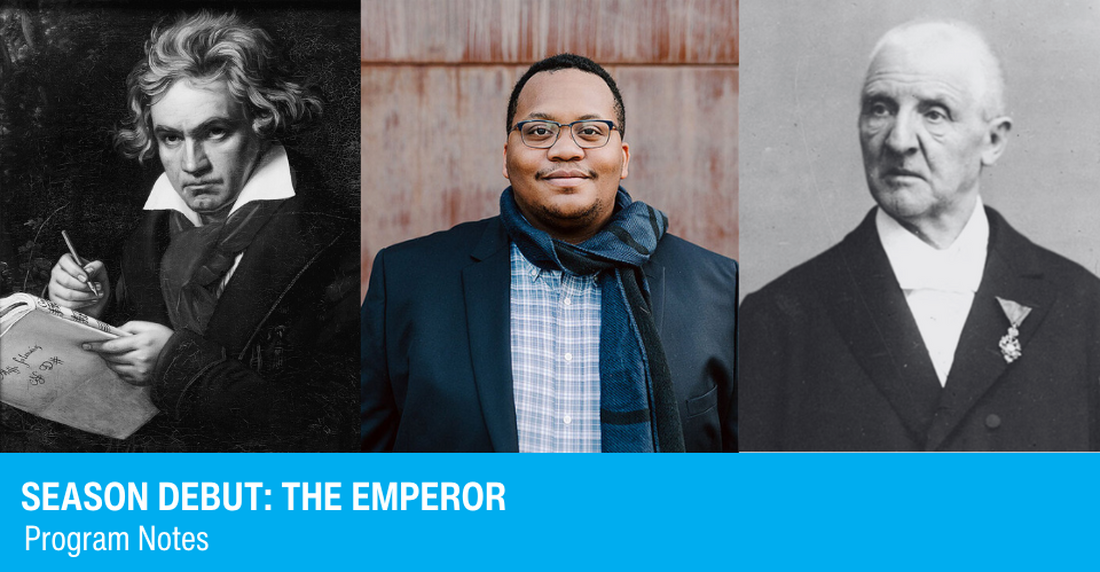

30 SECOND NOTES: Kevin Day is among the youngest of the remarkable generation of gifted American composers bringing new voices and renewed energy to the concert hall. At just 28, he has composed hundreds of works that have been performed internationally, received numerous honors, conducted, performed, led a professional organization, and been commissioned to write an opera for premiere on Juneteenth 2025 in Cincinnati. Day’s vibrant Lightspeed opens the Des Moines Symphony’s 2024-2025 season. Ludwig Van Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto, one of his most masterful works, was composed during the upheavals of the Napoleonic invasion of Vienna. The orchestral works of Austrian composer, organist and teacher Anton Bruckner have been called “cathedrals in sound” because of their vast proportions and heaven-reaching sonorities. Bruckner waited years to have his works accepted, and he finally won his first success with the Seventh Symphony, premiered when he was sixty years old.

KEVIN DAY

- Born February 23, 1996 in Charleston, West Virginia.

LIGHTSPEED: FANFARE FOR ORCHESTRA

- First performed on November 14, 2019 in Lexington, Virginia by the Washington and Lee University Orchestra, conducted by Chris Dobbins.

- This piece was first performed by the Des Moines Symphony at their annual Youth Concerts on March 5 & 6, 2024.

(Duration: ca. 3 minutes)

In 2019, when he was 23, Kevin Day composed a concert opener that is emblematic of his budding career — Lightspeed. Since then, Day has written well over 120 pieces for piano, accompanied solo instruments, orchestra, chorus, chamber ensembles, concert band (both professional and educational), film, electronics and jazz ensemble that encompass the influences of jazz, minimalism, Latin music, R&B, fusion and contemporary classical. He is currently working on Lalovavi: An Afro-Futurist Opera in Three Acts, the first of three commissions to all-Black creative teams from the Cincinnati Opera and the Mellon Foundation; Lalovavi is scheduled for its premiere during Juneteenth 2025.

For a young composer at the beginning of his career, Day has scored a remarkable range and number of accomplishments — he has received a MacDowell Fellowship, BMI Composer Award, First Prize in the Atlanta Philharmonic Orchestra Composition Contest, and Alumni Outstanding Young Professional Award from Texas Christian University; been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize; held numerous residencies and fellowships across the country; conducted many school and university ensembles, including an appearance at New York’s Carnegie Hall in 2022; performed as a jazz pianist; served as Vice President of the Millennium Composers Initiative (a collective of composers from different countries and backgrounds); and had works performed on five continents by school and university ensembles as well as such preeminent organizations as the National Orchestra of Spain, the major orchestras of Boston, Cincinnati, Detroit, Fort Worth, Indianapolis, Houston and San Francisco, and the flagship bands of four United States military services — Marines, Navy, Army and Air Force.

Kevin Day, born in Charleston, West Virginia in 1996 and raised in Arlington, Texas, was immersed in music from infancy — his father is a prominent hip-hop producer from Southern California and his mother an admired gospel singer from West Virginia who directed the music at the family’s church — and he started to compose while still in high school. Day majored in tuba and euphonium performance and received his first formal composition training as an undergraduate at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. He has gone on to earn a Master’s Degree in composition at the University of Georgia and a Doctor of Musical Arts at the University of Miami. From 2022 to 2024, he taught composition and led the jazz orchestra at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada. He currently lives in San Diego.

Day said that the title and spirit of Lightspeed: Fanfare for Orchestra, commissioned in 2019 by the Washington and Lee University Orchestra, were influenced by his love of Star Trek and Doctor Who. Lightspeed, brilliantly scored, bursts with optimism and energy, balancing bracing rhythmic statements for full orchestra with lyrical passages in the strings to give the piece a fine formal balance in its complementary moods and styles.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, woodblock, piano and the usual strings consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

- Born December 16, 1770 in Bonn;

- died March 26, 1827 in Vienna.

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 5 IN E-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 73, "EMPEROR"

- First performed on November 11, 1811 in Leipzig, conducted by Johann Philipp Schulz with Friedrich Schneider as soloist.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on November 6, 1950 with Frank Noyes conducting and Claudio Arrau as soloist. Nine subsequent performances occurred, most recently on September 21 & 22, 2018 with Joeseph Giunta conducting and Inon Barnaton as soloist.

(Duration: ca. 40 minutes)

The year 1809 was a difficult one for Vienna and for Beethoven. In May, Napoleon invaded the city with enough firepower to send the residents scurrying and Beethoven into the basement of his brother’s house. The bombardment was close enough that he covered his sensitive ears with pillows to protect them from the concussion of the blasts. On July 29, he wrote to the publisher Breitkopf und Härtel, “We have passed through a great deal of misery. What a disturbing, wild life around me; nothing but drums, cannons, men, misery of all sorts.” Austria’s finances were in shambles, and the annual stipend Beethoven had been promised by several noblemen who supported his work was considerably reduced in value, placing him in a precarious pecuniary predicament. As a sturdy tree can root in flinty soil, however, a great musical work grew from those unpromising circumstances — by the end of 1809 Beethoven had completed his “Emperor” Concerto.

The Concerto opens with broad chords for orchestra answered by piano before the main theme is announced by the violins. The following orchestral tutti embraces a rich variety of secondary themes leading to a repeat of all the material by the piano accompanied by the orchestra. A development ensues with “the fury of a hail-storm,” wrote noted English musicologist Sir Donald Tovey. A recapitulation of the themes and a cadenza close the movement. The Adagio begins with a chorale for strings. Sir George Grove, of music encyclopedia fame, dubbed this movement a sequence of “quasi-variations,” with the piano providing a coruscating filigree above the orchestral accompaniment. This Adagio leads directly into the Finale, a vast rondo with sonata elements.

The score calls for piccolo, flutes, clarinets, oboes, and bassoons in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, timpani, and the usual strings.

ANTON BRUCKNER

- Born Septmber 4, 1824 in Ansfelden, upper Austria;

- died October 11, 1896 in Vienna.

SYMPHONY NO. 7 IN E MAJOR

- First performed on December 30, 1884 in Leipzig, conducted by Arthur Nikisch.

- First and most recently performed by the Des Moines Symphony on May 7 & 8, 1983 with Yuri Krasnapolsky conducting.

(Duration: ca. 65 minutes)

Anton Bruckner was an unlikely figure to be at the center of 19th-century music’s fiercest feud. He was a country bumpkin from Linz — with his shabby peasant clothes, his rural dialect, his painful shyness with women, his naive view of life — in one of the world’s most sophisticated cities, Vienna. Bruckner had the glory — and the curse — to have included himself among the ardent disciples of Richard Wagner, and his fate was indissolubly bound up with that of his idol from the time he dedicated his Third Symphony to him in 1877.

While “Bayreuth Fever” was infecting most of Western civilization during the last quarter of the 19th century, there was a strong anti-Wagner clique in Vienna headed by the critic Eduard Hanslick, a virulent spokesman against emotional and programmatic display in music who championed the cause of Brahms and never missed a chance to fire a blazing barb at the Wagner camp. Bruckner, teaching and composing in Vienna within easy range of Hanslick’s vitriolic pen, was one of his favorite targets. He called Bruckner’s music “unnatural,” “sickly,” “inflated” and “decayed,” and intrigued to stop the performance of his works whenever possible. Bruckner felt that much of the rejection his symphonies suffered early in his career could be attributed to Hanslick’s slashing reviews.

Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony is intimately linked with his devotion to Wagner. Like all of his instrumental works, it aims at adapting Wagner’s theories and harmonic and instrumental techniques to absolute music and securing a place for them in the symphony. In addition to this general influence, the Seventh Symphony bears an even more direct connection with the Master of Bayreuth. About a year after Bruckner had begun work on the score in September 1881, reports of Wagner’s deteriorating health began to filter back to Vienna from Venice, where Wagner had gone to escape the harsh German climate. Bruckner later wrote to his friend and devoted pupil Felix Mottl concerning the fall of 1882, “At one time, I came home and was very sad. I thought to myself, it is impossible that the Master can live long. It was then that the music for the Adagio of my Symphony came into my head.” To make the tribute unmistakable, Bruckner made the dominant orchestral sonority in the movement a quartet of “Wagner tubas” (brass instruments of burnished tone color that are a cross between the horn and the euphonium), which were designed especially by Wagner for use in his operas. Most of the slow movement was already sketched when the news of Wagner’s death on February 13, 1883 reached Bruckner, and he added the concluding section specifically as a memorial to his idol. Later, he referred to this magnificent Adagio as “Funeral Music — a Dirge to Wagner’s Memory.” It was fitting that this music should also have been played a dozen years later at Bruckner’s own funeral in Vienna and his burial in St. Florian.

After the death of Wagner, Bruckner went ahead with the Seventh Symphony, and completed the score in September 1883. Arthur Nikisch, then only 29 and already moving into a dominant position as one of the era’s great conductors, planned the premiere with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in June 1884, but the performance had to be put off twice. Not only did Nikisch have to overcome the resistance of the anti-Wagner/Bruckner faction, but he also had to deal with the conservative Gewandhaus administration, which refused to have anything to do with the affair and insisted that it be moved to another theater. They missed staging a hit, the first unspoiled acclaim Bruckner had ever known. A good deal of the Symphony’s success must be credited to Nikisch, not just because he gave a splendid reading of the new work, but also because he invited the local critics to his home a few days before the premiere so that he could familiarize them with the music at the piano. Bruckner was moved and overjoyed by his reception in Leipzig, as one unnamed critic reported: “One could see from the trembling of his lips, and the sparkling moisture in his eyes, how difficult it was for the old gentleman to suppress his deep emotion. His homely but honest countenance beamed with a warm inner happiness. Having heard this work and now seeing him in person, we asked ourselves in amazement, ‘How is it possible that he could remain so long unknown to us?’”

The Symphony made a triumphant procession through the major German cities. The Munich premiere in early 1885 was so rapturously received that its conductor, Hermann Levi, called the composition “the most significant symphonic work since [the death of Beethoven in] 1827.” This encomium not only praised Bruckner but was also a slap at Brahms, whose Third Symphonyhad appeared just two years earlier. Though the work received the expected critical battering when it reached Vienna, the public was finally willing to grant the patient Bruckner his due, and he was recalled to the stage three or four times after each movement by the applause. Among the audience at the Viennese premiere was Johann Strauss the Younger, King of the Waltz, who desperately wanted to write a successful grand opera and be recognized as a “serious composer.” Strauss sent a telegram to Bruckner with a terse, but meaningful message: “Am much moved — it was the greatest impression of my life.”

The opening movement of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony is on the grand, architectural scale that characterizes the greatest of his works. Its three themes occupy broad paragraphs that give the music a transcendent spaciousness unmatched by the creations of any other composer. The long opening theme is succeeded by a more lyrical motive with a turn figure (a favorite melodic device of Wagner). After one of Bruckner’s characteristic ringing climaxes, the movement’s third theme appears, a quiet but somewhat heavy peasant dance presented in near-unison. The development section begins with an inversion of the opening theme, after which the various melodies of the exposition are again assayed. The recapitulation commences quietly and without preparation, and includes the earlier themes in heightened settings. The coda is based on the first motive and rises to a stentorian close.

The Adagio, Bruckner’s moving memorial tribute to Richard Wagner, consists of two large stanzas of music that alternate to form a five-part musical structure: A–B–A–B–A. The “A” section is dominated by a solemn chorale. The contrasting music is brighter in mood, with a hint of the lilting Austrian country dance, the Ländler. The tension is controlled through the long span of this movement with consummate mastery by pacing each return of the chorale theme so that it is more magnificent than the preceding presentation.

The third movement is one of Bruckner’s great Scherzos. A powerful, ostinato-like rhythm supports the open-interval theme. The movement’s motives are combined and developed with an irresistible urgency as the movement unfolds. The central trio is slower in tempo, sweeter in mood, and lyrical in style.

The Finale is based on two thematic elements: a dotted-rhythm motive and a hymnal theme over a wide-ranging pizzicato bass line. The movement follows a broad sonata outline, with some climaxes based on the dotted-rhythm melody. To round out the Symphony’s structure, the opening theme of the first movement is superimposed on the closing pages of the Finale.

The score calls for piccolo, flutes, clarinets, oboes, and bassoons in pairs, four horns, four Wagner tubas, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle, and the usual strings.