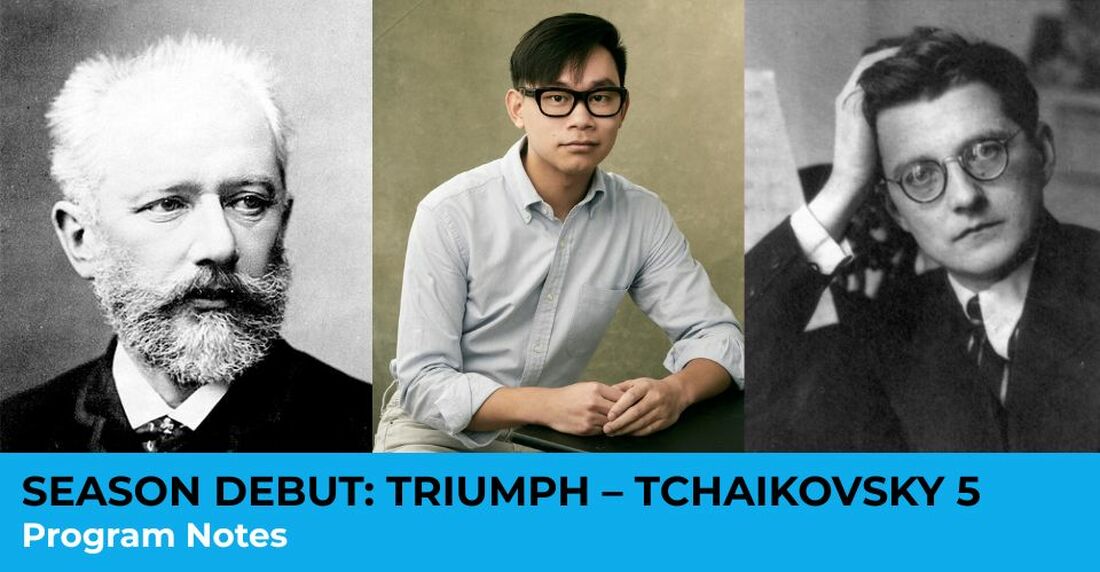

30 SECOND NOTES: Dmitri Shostakovich composed the Festive Overture in 1954 to commemorate the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but the celebratory nature of the work may also have expressed his relief following the death of Joseh Stalin a year before, which ended the dictator’s repressive artistic policies. The music of Viet Cuong, California-born son of Vietnamese immigrants, is rooted deeply in his life and beliefs — Re(new)al (played here two seasons ago) grew from his “respect for renewable energy initiatives and the commitment to creating a new, better reality for us all”; John and Jim was inspired by the Obergefell Supreme Court case that legalized same-sex marriage; and Vital Sines, scored mostly for wind instruments, is a tribute to the concert bands of his childhood, which profoundly shaped his musical, family and social lives. The Symphony No. 5 of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky follows the expressive path blazed by Beethoven in his Fifth Symphony, which progressed from an unsettled state to an affirmative one, from dark to light, from minor to major, a process described by Lawrence and Elisabeth Hanson in their biography of Tchaikovsky as “a spiritual power which subjects man to checks and agonies for the betterment of his soul.”

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH

Born September 25, 1906 in St. Petersburg;

died August 9, 1975 in Moscow.

FESTIVE OVERTURE, OP. 96

- First performed on November 7, 1954 at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, conducted by Vassili Nebolsin.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on September 12, 2009 with Bright Sheng conducting. One subsequent performance occurred on April 27 & 28, 2019 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 6 minutes)

Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. Shostakovich was convinced that Stalin was behind the painful censures he had received in 1936 and 1948, and he had determined after the second episode not to issue any substantive works until the dictator was gone. The superb Tenth Symphony, completed within months of Stalin’s passing on March 5, 1953, served as a testament of Shostakovich’s renewed artistic creativity, and the composer Dmitri Kabalevsky noted that the finale of that work “has much in common with the Festive Overture (including the basic melodic seeds).” One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.”

As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. It begins with a stentorian proclamation from the brass as preface to the racing main theme of the piece. Contrast is provided by a broad melody initiated by the horns, but the breathless celebration of the music continues to the end.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, three oboes, three clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle and the usual strings consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

VIET CUONG

Born September 8, 1990 in West Hills, California.

VITAL SINES

- First performed on April 9, 2022 at the Schlesinger Concert Hall in Alexandria, Virginia by Eighth Blackbird and the US Navy Band.

- These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 16 minutes)

Viet Cuong, the son of Vietnamese immigrants, was born in 1990 in West Hills, California, north of Malibu, but grew up in Marietta, Georgia, where the school music program gave him both a love of music and a sense of belonging. He studied composition at the Peabody Institute, Princeton University and Curtis Institute of Music with such eminent composers as Jennifer Higdon, Kevin Puts, Steven Mackey, Jennifer Higdon, David Serkin Ludwig and Richard Danielpour, and received additional training at the Orchestra of St. Luke’s DeGaetano Institute, Minnesota Orchestra Composers Institute, Mizzou International Composers Festival, Eighth Blackbird Creative Lab, Cabrillo Festival’s Young Composer Workshop, Cortona Sessions, Copland House’s CULTIVATE workshop, and Aspen and Bowdoin Music Festivals. Cuong is now Assistant Professor of Composition at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and the Pacific Symphony’s Composer-in-Residence; he previously held artist residencies at the California Symphony, Yaddo, Ucross, Atlantic Center for the Arts and Dumbarton Oaks, where he served as the Early-Career Musician-in-Residence. Cuong’s eclectic compositions, which draw inspiration from and even incorporate everyday sounds and objects — a snare drum played with a hair comb and a credit card; Re(new)al opens with an ensemble of tuned crystal wine glasses — have been performed internationally by such diverse ensembles as the New York Philharmonic, Alarm Will Sound, Sō Percussion, United States Navy Band and PRISM Saxophone Quartet. Among Cuong’s growing list of honors are the Frederick Fennell Prize, Walter Beeler Memorial Prize, Barlow Endowment Commission, ASCAP Morton Gould Composers Award, Theodore Presser Foundation Award, Cortona Prize, New York Youth Symphony First Music Commission, and Boston GuitarFest Composition Prize.

Viet Cuong wrote of Vital Sines, composed in 2022 on commission from the US Navy Band to perform with Eighth Blackbird as soloists, “It would be difficult to overstate how important the wind ensemble has been in my life. Band was where I found community and identity during a time in my youth when I feared that there was nothing out there for me. It was one of the only places during those teenage years where I felt confident in who I was. And it was ultimately this confidence that gave me the nerve to believe that I could one day make it as a composer.

“But my life in the wind ensemble world almost never was. I very nearly gave up my musical pursuits in a fit of childhood frustration at the age of eleven. My father, though he had no musical ability himself, saw in it something important. Always one to look after my creativity, he steadied me and encouraged me to give it more time. It was not long before he was proven right, and music had become something vital to me.

“I find myself thinking of that crucial moment more and more since my father’s passing, and how music was and remains my vital connection to him. I have come to understand that my love for music is inseparable from the love I have for my father.

“Vital Sines is dedicated to my father’s memory as well as the many moments during my life when I found sanctuary in music. The creation of this piece, though challenging, was a way of finding solace when I needed it most. Throughout the piece, I employ several musical sequences and chaconne forms, all of which use repetition as a means of development. The overarching structure of the piece thus bears a resemblance to the visual depiction of the sine wave, rising and falling like the tracing of breaths and heartbeats. There is, of course, comfort in the familiarity of continued repetition. But I also followed memories back to my teenage years in Band, when that community had the extraordinary ability not just to bring me comfort but to heal my heart. What I then realized was that all the other musical communities I have become a part of since then, Band or not, hold this same healing power.”

The score calls for piccolo, three flutes, two oboes, English horn, two bassoons, three clarinets, bass clarinet, contrabass clarinet, soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, three trumpets, four horns, three trombones, euphonium, tuba and bass drum, cymbals, snare drums, glockenspiel, vibraphone, chimes, crotales and triangle.

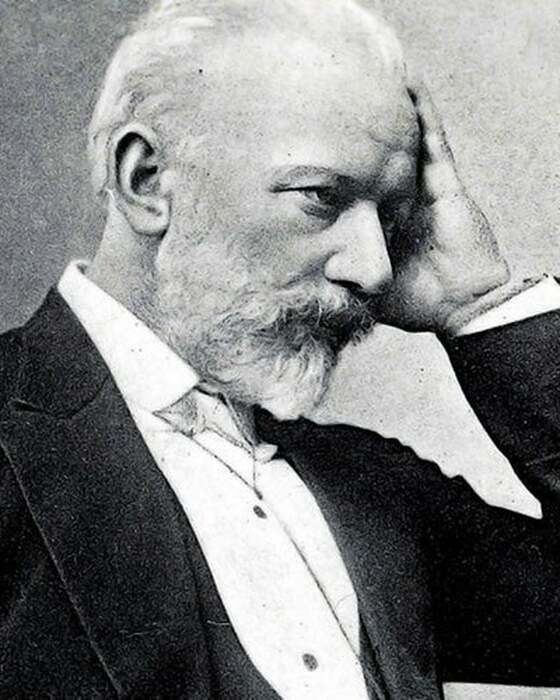

PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

Born May 7, 1840 in Votkinsk;

died November 6, 1893 in St. Petersburg.

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

- First performed on November 17, 1888 in St. Petersburg, conducted by the composer.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on March 27, 1939 with Frank Noyes conducting. Six subsequent performances occurred, most recently on May 21 & 22, 2016 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 45 minutes)

Tchaikovsky, like most creative artists, often had episodes of self-doubt. More than once, his opinion of a work fluctuated between the extremes of satisfaction and denigration. The unjustly neglected Manfred Symphony of 1885, for example, left his pen as “the best I have ever written,” but the work failed to make a good impression at its premiere and Tchaikovsky’s estimation of it tumbled. The lack of success of Manfred was particularly painful, because he had not produced a major orchestral work since the Violin Concerto of 1878, and the score’s failure left him with the gnawing worry that he might be “written out.” The three years after Manfred were devoid of creative work. It was not until May 1888 that Tchaikovsky again took up the challenge of the blank page, collecting “little by little, material for a symphony,” he wrote to his brother Modeste. Tchaikovsky worked doggedly on the new symphony, ignoring illness, the premature encroachment of old age (he was only 48, but suffered from continual exhaustion and loss of vision), and his doubts about himself. He pressed on, and when the orchestration of the Fifth Symphony was completed, at the end of August, he said, “I have not blundered; it has turned out well.”

Tchaikovsky never gave any indication that the Symphony No. 5, unlike the Fourth Symphony, had a program, though he may well have had one in mind. In their biography of the composer, Lawrence and Elisabeth Hanson reckoned Tchaikovsky’s view of fate as the motivating force in the Symphony No. 5, though they distinguished its interpretation from that in the Fourth Symphony. “In the Fourth Symphony,” the Hansons wrote, “the Fate theme is earthy and militant, as if the composer visualizes the implacable enemy in the form, say, of a Greek god. In the Fifth, the majestic Fate theme has been elevated far above earth, and man is seen, not as fighting a force that thinks on its own terms, of revenge, hate, or spite, but a wholly spiritual power which subjects him to checks and agonies for the betterment of his soul.”

The structure of the Fifth Symphony reflects this process of “betterment.” It progresses from minor to major, from darkness to light, from melancholy to joy — or at least to acceptance and stoic resignation. The Symphony’s four movements are linked together through the use of a recurring “Fate” motto theme, given immediately at the beginning by unison clarinets as the brooding introduction to the first movement. The sonata form proper starts with a melancholy melody intoned by bassoon and clarinet over a stark string accompaniment. Several themes are presented to round out the exposition: a romantic tune, filled with emotional swells, for the strings; an aggressive strain given as a dialogue between winds and strings; and a languorous, sighing string melody. All of the materials from the exposition are used in the development. The solo bassoon ushers in the recapitulation, and the themes from the exposition are heard again, though with appropriate changes of key and instrumentation.

At the head of the manuscript of the second movement Tchaikovsky is said to have written, “Oh, how I love … if you love me…,” and, indeed, this wonderful music calls to mind an operatic love scene. (Tchaikovsky, it should be remembered, was a master of the musical stage who composed more operas than he did symphonies.) Twice, the imperious Fate motto intrudes upon the starlit mood of this romanza.

If the second movement derives from opera, the third grows from ballet. A flowing waltz melody (inspired by a street song Tchaikovsky had heard in Italy a decade earlier) dominates much of the movement. The central trio section exhibits a scurrying figure in the strings. Quietly and briefly, the Fate motto returns in the movement’s closing pages.

The finale begins with a long introduction based on the Fate theme cast in a heroic rather than a sinister or melancholy mood. A vigorous exposition, a concentrated development and an intense recapitulation follow. The long coda uses the motto theme in its major-key, victory-won triumphant conclusion.

The score calls for flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons in pairs, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, glockenspiel, chimes, triangle, China cymbal, bass drum, crotales and the usual strings.