Read about the music and composers featured in Masterworks 6: Beethoven's Ninth on April 9 & 10, 2022.

The philosophical power of Beethoven’s music is distilled nowhere better than in the two works on this concert. Both the Leonore Overture No. 3 and the Ninth Symphony are quests that musically represent the striving toward an ideal, toward a humanity drawn to our “better angels.” The expressive path of each work rises from minor to major, from darkness to light, from struggle to resolution, from subjugation to freedom. Complementing them on this program is Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s evocation of Medieval mysticism in his Fratres and Richard Wagner’s vision of love that transcends life itself in his epochal Tristan und Isolde.

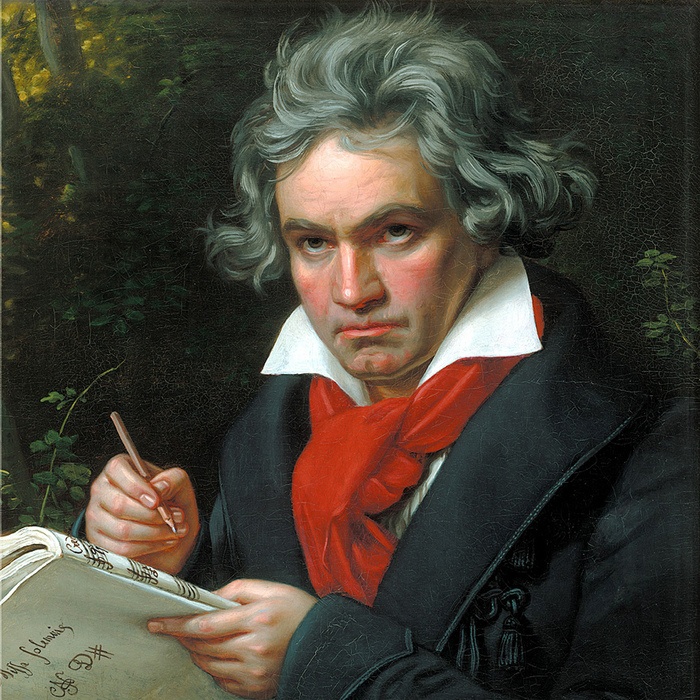

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born December 16, 1770 in Bonn;

died March 26, 1827 in Vienna.

LEONORE OVERTURE NO. 3, OP. 72B

• First performed on March 29, 1806 in Vienna, conducted by Ignaz von Seyfried.

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on November 11, 1951 with Frank Noyes conducting. Subsequently performed eight times, most recently on March 26 & 27, 2011 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 14 minutes)

The most visible remnants of the extensive revisions to which Beethoven subjected his Fidelio between 1804 and 1814 are the four overtures he composed for the opera. For the first version, composed in 1804-1805, Beethoven wrote the Overture in C Major now known as the Leonore No. 1, utilizing themes from the opera. The composer’s friend and early biographer Anton Schindler recorded that Beethoven rejected that first attempt after hearing it privately performed at Prince Lichnowsky’s palace before the premiere, so he composed a second C major overture, Leonore No. 2, and that piece was used at the first performance, on November 20, 1805. The opera foundered. Beethoven was encouraged by his aristocratic supporters to rework the opera and present it again. The second version, for which the magnificent Leonore Overture No. 3 was written, was presented in Vienna on March 29, 1806 but met with little more acclaim than its forerunner. In 1814, some members of the Court Theater convinced Beethoven to revive Fidelio yet again. The new Fidelio Overture, the fourth he composed for his opera, was among the revisions.

The Leonore No. 3 distills the essential dramatic progression of the opera into purely musical terms: the triumph of good over evil, the movement from darkness to light, from subjugation to freedom, is integral to this music.

The score calls for flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and the usual strings consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

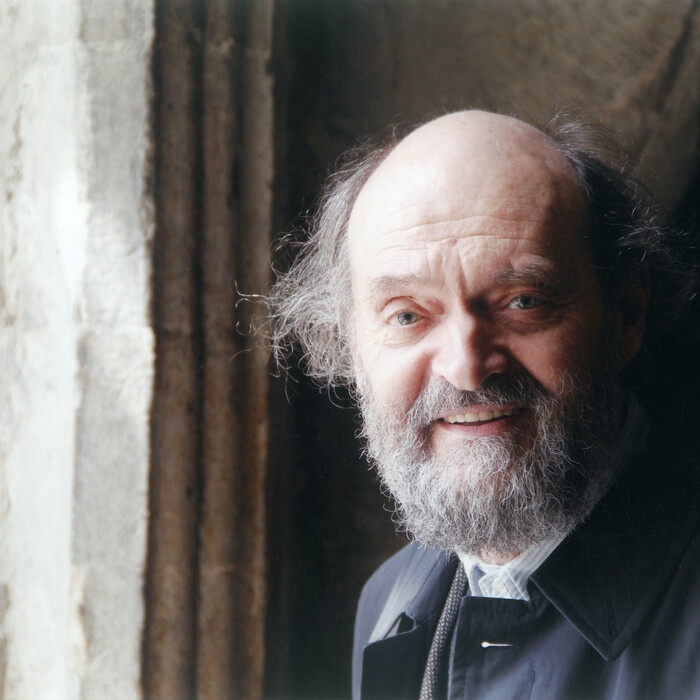

Arvo Pärt

Born September 11, 1935 in Paide, Estonia.

FRATRES (“BROTHERS”)

• Orchestral version first performed on April 29, 1983 in Stockholm, conducted by Neeme Järvi.

• These concerts mark the first performance of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 10 minutes)

Arvo Pärt, born in 1935 in Paide, Estonia, fifty miles southeast of Tallinn, graduated from the Tallinn Conservatory in 1963 while working as a recording director in the music division of the Estonian Radio. A year before leaving the Conservatory, he won first prize in the All-Union Young Composers’ Competition for a children’s cantata and an oratorio. In 1980, he emigrated to Vienna, where he took Austrian citizenship; he moved to Berlin in 1982 and later returned to Tallinn. Pärt’s many distinctions include the Artistic Award of the Estonian Society in Stockholm, honorary memberships in the Royal Swedish Academy of Music, American Academy of Arts and Letters, and Belgium’s Royal Academy of Arts, seven Grammy nominations, and recognition as a Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française. In his early works, Pärt explored the influences of the Soviet music of Prokofiev and Shostakovich, the serial principles of Schoenberg, and the techniques of collage and quotation, but in the late 1960s he abandoned creative work for several years to devote himself to the study of such Medieval and Renaissance composers as Machaut, Ockeghem, Obrecht and Josquin. Guided by the spirit and method of those ancient masters, Pärt developed a distinctive idiom that utilizes quiet dynamics, rhythmic stasis and open-interval and triadic harmonies to create a thoughtful mood of mystical introspection reflecting the composer’s personal piety.

Fratres was composed in 1977 for string quintet and wind quintet, and adapted for strings and percussion in 1983. Fratres is based on the repetitions of an austere, hymnal theme played above a continuous drone on the interval of an open fifth. The repetitions, separated by notes played as or simulating drum taps, are transposed downward by the interval of a minor or major third on each appearance, so that the sonority grows lower and richer as Fratres unfolds. The dynamic peak is reached in the middle of the work, after which the music is gradually overtaken by silence to end in a state of hushed spirituality. The work’s title — “Brothers” — seems to indicate that this music was inspired by the vision of a solemn procession of Medieval monks, wending their way by flickering candlelight along the ambulatory to the abbey’s chapels for another of the endless succession of services that regulated their monastic lives.

The score calls for bass drum, claves and the usual strings.

RICHARD WAGNER

Born May 22, 1813 in Leipzig;

died February 13, 1883 in Venice.

“LIEBESTOD” (“LOVE-DEATH”) FROM TRISTAN UND ISOLDE FOR SOPRANO & ORCHESTRA

• First performed on June 10, 1865 in Munich, conducted by Hans von Bülow

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on November 5, 1953 with Frank Noyes conducting and Helen Traubel as soloist. Subsequently performed three times, most recently on February 12 & 13, 2011 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 7 minutes)

Wagner provided a synopsis of the emotional progression of the action of Tristan whose voluptuous prose is a not only a sketch of the events of the story, but also a key to understanding the sea of passion upon which the entire world of this opera floats:

“Tristan, the faithful vassal, woos for his king, her for whom he dares not avow his own love, Isolde. Isolde, powerless to do otherwise than obey the wooer, follows him as bride to his lord. Jealous of this infringement of her rights, the Goddess of Love takes her revenge. As the result of a happy mistake, she allows the couple to taste of the love potion which, by the burning desire which suddenly inflames them after tasting it, opens their eyes to the truth and leads to the avowal that for the future they belong only to each other. Henceforth, there is no end to the longings, the demands, the joys and woes of love. One thing only remains: longing, longing, insatiable longing, forever springing up anew, pining and thirsting. Powerless, the heart sinks back to languish in longing, in longing without attaining; for each attainment only begets new longing, until in the last stage of weariness the foreboding of the highest joy of dying, of no longer existing, of the last escape into that wonderful kingdom from which we are furthest off when we are most strenuously striving to enter therein. Shall we call it death? Or is it the hidden wonder-world from out of which an ivy and vine, entwined with each other, grew up upon Tristan’s and Isolde’s grave, as the legend tells us?”

The Liebestod generates a magnificent tonal gratification at the point near the end of the opera where the lovers find their only possible satisfaction in welcome death. Of this sublime moment, Wagner wrote, “What Fate divided in life now springs into transfigured life in death: the gates of union are thrown open. Over Tristan’s body the dying Isolde receives the blessed fulfillment of ardent longing, eternal union in measureless space, without barriers, without fetters, inseparable.”

The score calls for two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, three bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, harp and the usual strings.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

SYMPHONY NO. 9 IN D MINOR, OP. 125, “CHORAL”

• First performed on May 7, 1824 in Vienna, conducted by Michael Umlauf under the composer’s supervision.

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on May 17, 1970 with Willis Page conducting, Margaret Hauptmann, soprano, Carolyn Stanford, mezzo-soprano, Jerry Jennings, tenor, and Charles Nelson, baritone as soloists and the Drake Choir. Subsequently performed seven times, most recently on September 24 & 25, 2016 with Joseph Giunta conducting, Carrie Ellen Giunta, soprano, Mary Creswell, mezzo-soprano, Scott Ramsay, tenor, Dashon Burton, baritone as soloists and with the Drake Choir, Simpson College Chamber Singers and Des Moines Vocal Arts Ensemble.

(Duration: ca. 70 minutes)

“I’ve got it! I’ve got it! Let us sing the song of the immortal Schiller!” shouted Beethoven to Anton Schindler, his companion and eventual biographer, as he burst from his workroom one afternoon in October 1823. The joyful announcement meant that the path to the completion of the Ninth Symphony — after a gestation of more than three decades — was finally clear.

Friedrich Schiller published his poem An die Freude (“Ode to Joy”) in 1785 as a tribute to his friend Christian Gottfried Körner. By 1790, when he was twenty, Beethoven knew the poem, and as early as 1793 he considered making a musical setting of it. Schiller’s poem appears in his notes in 1798, but the earliest musical ideas for its setting are found among the sketches for the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies, composed simultaneously in 1811-1812. Though these sketches are unrelated to the finished Ode to Joy theme — that went through more than 200 revisions (!) before Beethoven was satisfied with it — they do show the composer’s continuing interest in the text and the gestating idea of setting it for chorus and orchestra. The Seventh and Eighth Symphonies were finished by 1812, and Beethoven immediately started making plans for his next composition in the genre, settling on the key of D minor, but getting no further. It was to be another dozen years before he could bring this vague vision to fulfillment.

The first evidence of the musical material that was to figure in the finished Ninth Symphony appeared in 1815, when a sketch for the theme of the Scherzo emerged among Beethoven’s notes. He took up his draft again in 1817, and by the following year much of the Scherzo was sketched. It was also in 1818 that he considered including a choral movement, but as the slow movement rather than as the finale. With much still unsettled, Beethoven was forced to lay aside this vague symphonic scheme in 1818 because of ill health, the distressing court battle to secure custody of his nephew, and other composing projects, most notably the monumental Missa Solemnis, and he was not able to resume work on the piece until the end of 1822. The 1822 sketches show considerable progress on the Symphony’s first movement, little on the Scherzo, and, for the first time, some tentative ideas for a choral finale based on Schiller’s poem.

In November 1822, a commission arrived from the London Philharmonic Society for a new symphony. Beethoven accepted it. For several months thereafter, he envisioned two completely separate works: one for London, entirely instrumental, to include the sketched first movement and the nearly completed Scherzo; the other to use the proposed choral movement with a German text, which he considered inappropriate for an English audience. He took up the “English Symphony” first, and most of the opening movement was sketched during the early months of 1823. The Scherzo was finished in short order by August, eight years after Beethoven first conceived its thematic material, and the third movement sketched by October. With the first three movements nearing completion, Beethoven found himself without a finale. His thoughts turned to the choral setting of An die Freude lying unused among the sketches for the “German Symphony,” and he decided to include it in the work for London, language notwithstanding. The “English Symphony” and the “German Symphony” had merged. The Philharmonic Society eventually received the symphony it had commissioned — but not until a year after it had been heard in Vienna.

Beethoven had one major obstacle to overcome before he could complete the Symphony: how to join together the instrumental and vocal movements. A recitative — the technique that had been used for generations to bridge from one operatic number to the next — that would be perfect, he decided. And the recitative could include fragments of themes from earlier movements — to unify the structure. “I’ve got it! I’ve got it!” he shouted with triumphant delight. Beethoven still had much work to do, as the sketches from the autumn of 1823 show, but he at last knew his goal, and the composition was completed by the end of the year. When the final scoring was finished in February 1824, it had been nearly 35 years since Beethoven first considered setting Schiller’s poem.

The Symphony begins with the interval of a barren open fifth, suggesting some awe-inspiring cosmic void. Thematic fragments sparkle and whirl into place to form the riveting main theme. A group of lyrical subordinate ideas follows. After a great climax, the open-fifth intervals return to begin the highly concentrated development section. A complete recapitulation and an ominous coda arising from the depths of the orchestra bring this eloquent movement to a close. The form of the second movement is a combination of scherzo, fugue and sonata that exudes a lusty physical exuberance and a leaping energy. The trio is more serene in character but forfeits none of the contrapuntal richness of the Scherzo. The Adagio is one of the most sublime pieces that Beethoven, or anyone else, ever wrote. Its impression of solemn profundity is enhanced by being placed between two such extroverted movements as the Scherzo and the Finale. Formally, this movement is a variation on two themes, almost like two separate kinds of music that alternate with each other.

The majestic closing movement is divided into two large parts: the first instrumental, the second with chorus and soloists. Beethoven chose to set about two-thirds of the original 96 lines of Schiller’s poem. To these, the composer added two lines of his own for the baritone soloist as a transition to the choral section. A shrieking dissonance introduces the instrumental recitative for cellos and basses that joins together brief thematic reminiscences from the three preceding movements. The wondrous Ode to Joy theme appears unadorned in the low strings, and is the subject of a set of increasingly powerful variations. The shrieking dissonance is again hurled forth, but this time the ensuing recitative is given voice and words by the baritone soloist. “Oh, friends,” he sings, “no more of these sad tones! Rather let us raise our voices together, and joyful be our song.” The song is the Ode to Joy, presented with transcendent jubilation by the chorus. Many sections based on the theme of the Ode follow, some martial, some fugal, all radiant with the glory of Beethoven’s vision.

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, triangle and the usual strings.