Read about the music and composers featured in Masterworks 3: The Planets on November 19 & 20, 2022. Program notes by Dr. Richard E. Rodda.

Edward Elgar said that his Cockaigne, named for the imaginary land of Medieval lore where life is an idler’s paradise, “calls to my mind all the good humour, jollity and something deeper in the way of English good fellowship.”

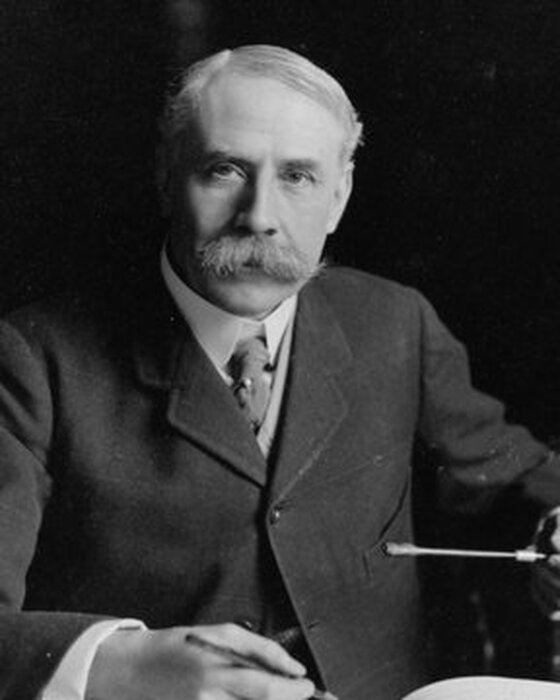

EDWARD ELGAR

Born June 2, 1857 in Broadheath, England;

died February 23, 1934 in Worcester.

COCKAIGNE (IN LONDON TOWN), CONCERT OVERTURE, OP. 40

• First performed on June 20, 1901 in London, conducted by the composer.

• These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 13 minutes)

“Cockaigne” (or, often, “Cockayne”) is the imaginary land of Medieval lore where life is an idler’s paradise: the rivers run with wine, the houses are built from sugar cakes, roast geese wander about waiting to be made a meal, buttered larks fall from the sky, and shopkeepers pass out their goods for free. The word apparently originated in the Latin coquere — “to cook” — and survives in the German term for “cake” — Kuchen; thus, “Cockaigne,” or “the land of cakes.” Despite its similarity, the name of the addictive drug, which derives from the coca plant, is unrelated in origin. Fabled Cockaigne figured in the literature of both Britain and France beginning in the 13th century, where it often provided the venue for satires visited upon clergy and others of high station with easy access to the good life. Though the word “Cockney” apparently came from an altogether different source (the Middle English cokeney, or “foolish person”), Cockaigne became associated with the residents of London’s East End (i.e., those born and raised, according to Cockney tradition, within the sound of the Bow Church bells), and, by extension, with the whole city of London.

In November 1900, a year after the triumph of his “Enigma” Variations had elevated him to the front rank of British composers, Edward Elgar reported that he was “one dark day in the Guildhall: while looking at the memorials of the city’s great past & knowing well the history of its unending charity, I seemed to hear far away in the dim roof a theme, an echo of some noble melody.” The theme that Elgar conjured from the spirits of the ancient Guildhall served as the catalyst for the Cockaigne Overture, which he subtitled “In London Town” when the score was completed the following March. He conducted the London Philharmonic in the work’s premiere, at Queen’s Hall on June 20, 1901, an event that his wife, Alice, told her diary was a “great glorious success.” Her opinion was echoed by the press: “the score is a masterpiece,” wrote one critic; “it is music that does one good to hear — invigorating, humanizing, uplifting,” wrote another. Cockaigne was performed in Boston within five months of its London premiere, and in Berlin (conducted by Richard Strauss) the following year. It became a staple of British concert programs, not least on those conducted by the composer himself, and has remained perhaps Elgar’s second most frequently performed work, behind only the ubiquitous Pomp and Circumstance Marches.

Though Elgar did not offer any specific program for Cockaigne, he wrote to the conductor Hans Richter, a leading proponent of his music, “Here is nothing deep or melancholy — it is intended to be honest, healthy, humorous and strong but not vulgar.” He told Joseph Bennett, who was preparing a program note for the Overture’s premiere, “It calls up to my mind all the good humour, jollity and something deeper in the way of English good fellowship (as it were) abiding still in our capital.”

The score calls for piccolo, flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons in pairs, contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tambourine, triangle, sleigh bells, organ and the usual strings.